Originally published on November 14, 2019 by Chris Quirk

Fraudulent wire transfers are an unfortunate reality in today’s business world, and as a result, many companies are now turning to insurance to help protect against these losses. The good news is that fraudulent wire transfers can be insured and the coverage is readily available at very affordable rates. The bad news is that placing the coverage correctly is very tricky, requiring significant expertise and attention to detail, so the chance of improper placement is high. In the marketplace today, coverage can be commonly found on a Commercial Crime insurance policy, or a Cyber Liability policy.

There are differing theories as to which policy should be the primary go-to solution when insuring these losses. Because in my view, the underlying loss is a theft of funds, I believe in a perfect world, the Crime policy should be the primary solution. However, the reality is that both Crime and Cyber policies can be adequately designed to cover these types of losses effectively. There is no general rule separating the two. You must carefully read each policy, whether it is Crime or Cyber, to determine the scope of coverage offered by that policy.

The main issue when analyzing these types of claims is that the coverage is very fact-dependent, and all policies differ greatly with how they insure the many different scenarios. Making matters worse, the coverages are often called very similar and interchangeable names that could easily confuse a buyer.

4 Key Factors to Understand

Whether coverage is provided by your Cyber Liability policy or your Commercial Crime policy, be sure to carefully read the applicable insuring agreement (as well as related terms and exclusions) covering fraudulent wire transfers.

There are 4 critical fact-based lynchpins upon which coverage often hinges. The terms of your policy will usually invoke one or more of them with the way the language is written. They are as follows:

- Whom did the hacker dupe with the fraudulent instruction? You or your Bank?

- Whose money was wired? Yours, or your client’s money?

- Whom did the hacker purport to be when issuing the fraudulent transfer instruction?

- What security protocols were in place at the time of the loss, and were they followed?

Keep in mind that when I reference “you” or “your” throughout this article, I am referring collectively to your company and its employees (not you personally). Just picture one or more employees performing the actions described in the fact patterns below. Once you understand these 4 critical questions, you are poised to become a master of Fraudulent Wire Transfer insurance.

Who was Duped by the fraudulent instruction – You or your Bank?

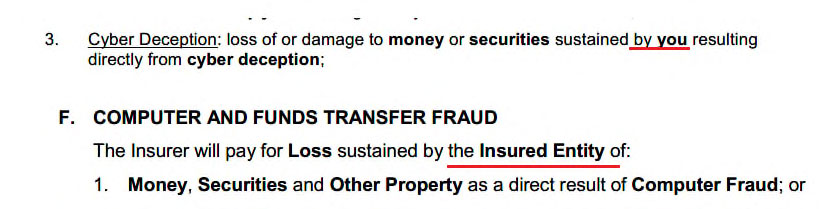

This question is important because virtually every policy I have seen provides two separate insuring agreements depending on who was duped by the hacker (often with different sublimits and coverage requirements). When the hacker dupes the bank directly, the applicable coverage is often called something like “Funds Transfer Fraud,” “Fraudulent Funds Transfer Loss,” or “Funds Transfer.” When the hacker dupes you, the applicable coverage is often called something like “Social Engineering Loss,” “Cyber Deception,” or “Fraudulent Instruction.” They look very much the same, and every insurance company uses a different title. However, the first thing you must think about when analyzing this loss is who was duped by the fraudulent instruction. A better way of thinking about it is who sent the instruction to the bank to wire the money, you or the hacker?

If you send the instruction to the Bank, that is a very different situation than if the hacker sends the instruction to the Bank.

Here are two very common scenarios:

1. A hacker accesses electronic communications stored on your mobile phone between you and your Bank because you were using an unsecured WiFi network at an airport while on a business trip. Within the accessed iles was a communication directing your Bank to issue payment for an invoice. You included your account info and an instruction for the Bank to wire $47,000 to a particular account in satisfaction of the invoice. Then, using your account, the hacker forwards a new communication to the Bank ordering a wire transfer of $95,000 to a bank account overseas. The only things that were changed were the destination account numbers and the referenced invoice number. The Bank, believing the request came from you, proceeds to wire the $95,000. 2 days later, you realize that you are missing $95,000.

In this scenario, the hacker sent the instruction to the Bank, and the Bank was duped. The Bank believed they were acting on a legitimate request from you when, in reality, they were acting on a fraudulent request sent in by the hacker. The Bank was duped by the fraudulent request, so this loss may be covered under the agreements titled “Funds Transfer Fraud,” “Fraudulent Funds Transfer Loss,” or “Funds Transfer,” (depending on how your insurer names the section). You or your employees were not duped in this example.

2. A hacker sends an urgent email to Sue from accounting pretending to be the company CFO, demanding that she wire $346,500 to a specific location or the company will lose out on an important contract, and she will be disciplined for not responding quickly. The hacker did a great job spoofing the CFO’s email & signature, and the email looks legitimate. Sue, fearing the repercussions if the company misses out on the contract, contacts the bank and orders the transfer pursuant to the email’s instructions. 2 days later, you discover that you are missing $346,500.

In this all too common situation, the fraudulent instruction went to Sue from accounting, who then acted upon it and ordered the Bank to wire the money. The difference in this scenario from the first is that the hacker did not contact the bank directly. The hacker tricked your employee Sue, who then sent a wire instruction to the Bank. The hacker did not send a fraudulent instruction to the Bank directly like in the first example. This situation may be covered under “Social Engineering Loss,” “Cyber Deception,” or “Fraudulent Instruction.”

The most important takeaway from this is that insurance policies distinguish between when the hacker sends the instruction to the Bank vs. when you send the instruction to the Bank, so you must also distinguish the two when doing your analysis. Coverage for one scenario will generally not apply to the other – a separate insuring agreement is needed.

In general, when the Hacker contacts and dupes the bank directly – this is typically covered only by a Commercial Crime policy. Very few, if any, cyber policies cover traditional “Funds Transfer Fraud,” where the hacker pretends to be you and succeeds in duping the bank into wiring money. Both Crime and Cyber policies routinely cover “Social Engineering,” where the hacker successfully dupes someone at the victim company.

Whose money was wired – Your’s or your Client’s?

This key question is only relevant to specific classes of business that routinely handle third-party funds in a trustee capacity. Trustees, funds administrators, and especially law firms are extremely susceptible to a coverage gap here. Assuming coverage is in place, the vast majority of Insurers will only provide coverage for the fraudulent wire transfer of your own money. Coverage will not apply to third-party funds held in trust on behalf of a client. So, for example, if the law firm of Lawyer & Lawyer LP suffers a fraudulent wire transfer loss involving the firm’s own funds, presumably, coverage will apply. If the fraudulent wire transfer loss affects the client’s funds stored in the firm’s client trust account, there will not be coverage for this under standard wire transfer insurance. The firm would require a highly specialized product to protect funds held in trust on behalf of third parties.

Here is an example.

As part of a multi-million dollar medical malpractice case, a client pays Lawyer & Lawyer a retainer of $700,000 to begin preliminary work. The firm has not yet earned these funds, and so the funds are deposited in the firm’s client trust account. As part of their investigation, the firm orders expensive scientific testing be done by a research lab. A hacker gains access to this correspondence and spoofs an invoice for the testing services in the amount of $40,000 which was in line with the original estimate provided by the lab. The firm then pays the fraudulent invoice from the $700,000 retainer held in the client trust fund.

Since these funds are the client’s funds and not the law firm’s, without specialized insurance coverage, this loss will likely be uninsured. If the firm carries standard wire transfer insurance through either a commercial cyber or crime policy, the loss will most likely be excluded.

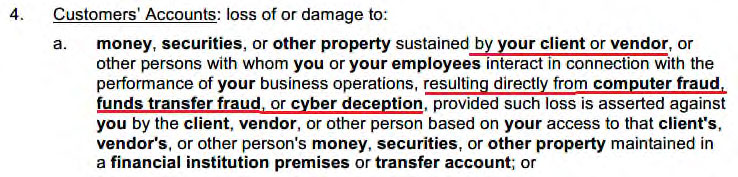

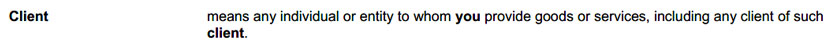

Here are two examples of policy language that would not cover the loss of your client’s funds. This language is standard on most policies offering fraudulent wire transfer coverage.

Insurers consistently take the position that the loss is sustained by your client, not by you (even though you are responsible), and so the above coverage sections cannot apply to loss of client funds.

Here is an example of a policy that extends coverage to funds you hold on a client’s behalf.

Here the coverage applies because the insurance specifically applies to loss sustained by your client or vendor, in contrast with the previous two examples. This coverage is not standard, and most insureds do not have it, even if many carry the exposure of handling client funds. In general, this specialized coverage is available only at low sub-limits (<$700k), though higher limits may be entertained on a case-by-case basis. You have to specifically request the coverage. Insurance companies do not just provide it by default, so be sure to ask for it prior to binding coverage.

Whom did the hacker purport to be?

When the hacker tricks the Bank directly, they always do so, purporting to be you. They have to impersonate you because you are the only one who can legitimately authorize a wire transfer from your bank. This factor comes into play when the hacker tricks you rather than your Bank. Many policies restrict who the hacker is allowed to impersonate before coverage can trigger. Coverage will only apply if the hacker purports to be someone who is explicitly listed by the policy. If you are duped by a hacker impersonating someone not specified by your policy, you are likely to have no coverage for the loss.

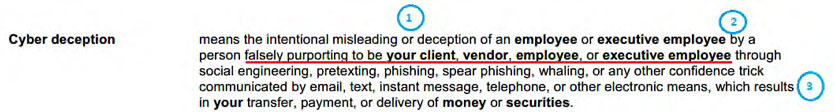

Here is a typical example found on many policies. Be sure to check the specific language on your policy, because all policies differ!

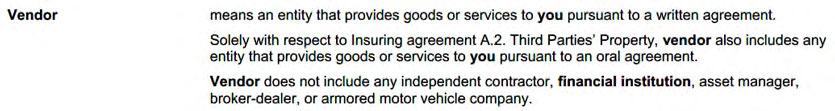

This insurer calls the coverage “Cyber Deception,” and the policy has 3 factual requirements needed to trigger coverage for wire transfer losses under this section. They are identified in the picture by the blue circles, and are as follows:

- The person who was misled into wiring the money must be an employee or executive employee;

- The hacker must falsely impersonate your client, vendor, employee, or executive employee; and

- The deception must result in the transfer of money or securities.

Requirements l and 3 are less critical because they occur naturally in the vast majority of fraudulent wire transfer losses. However, requirement 2 specifically requires that the hacker must try to impersonate someone that is included in the four bolded terms: client, vendor, employee, and executive employee. If the hacker impersonates an individual not included in this list, coverage will not apply. Let’s identify who might not be included in these definitions to see in what situations the insurance might not respond.

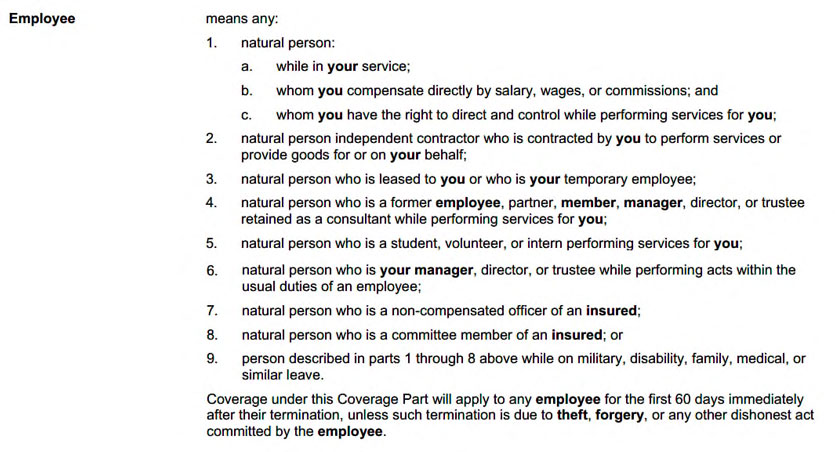

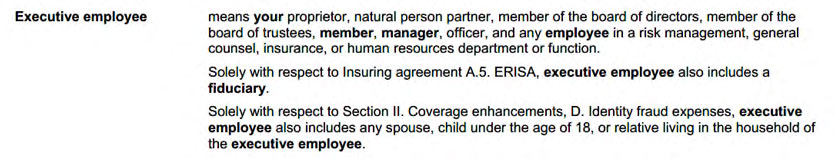

Here are the definitions.

Consider the following scenario, where the hacker’s purported identity will change to various parties with different effects on coverage, due to how the facts interact with requirement 2.

A hacker sends an urgent email to Sue from accounting pretending to be [XXXX] demanding that she wire $750,000 to a specific account or something bad will happen. The hacker did a great job spoofing the email and signature, and it looks legitimate. Sue, fearing the repercussions if she does not comply, contacts the bank and orders the transfer pursuant to the email’s instructions. 2 days later, you discover that you are missing $750,000.

POSSIBILITIES –

1. Hacker impersonates your company’s CFO, saying the company will miss out on an important contract and that Sue will be reprimanded if this happens.

You must run the specifics of the fact pattern through each definition to see if the company CFO is covered. The company CFO falls within the scope of executive employee, and so based on the logic of the coverage section, the insurance would apply because our employee (Sue from Accounting) was tricked by a hacker purporting to be an executive employee (the company CFO) leading to a fraudulent transfer of $750,000. Coverage would likely apply here.

2. Hacker impersonates Brian, an account manager at BizConsulting Inc. (a company who provides market consulting services to your company) following up for payment of a recent invoice (the hacker then sends you a fraudulent invoice with edited account information). The Hacker says that services will be interrupted if payment is not made with haste.

Run the fact pattern through the four definitions to see if coverage applies to an account manager at a company that provides services to you. Brian would not be considered an employee or executive employee because he, unlike the CFO, is not employed by your company. However, Brian’s company does provide consulting services to you, and so they might qualify as a vendor, which requires that a company provide goods or services to you. “pursuant to a written agreement.” So, if your company has a written consulting agreement with BizConsulting Inc., coverage will likely apply because the hacker purported to be a vendor. If you don’t have a written agreement in place, coverage is likely going to be declined because the requirements of the vendor definition are not met (there is no written agreement), and so BizConsulting Inc. could not qualify as a vendor. (The section covering oral agreements won’t save you in this claim because it applies solely to a different insuring agreement than the one covering fraudulent wire transfer loss.)

If you are asking yourself what a written agreement has to do with a wire transfer loss, such that coverage hinges upon the issue, the only thing I can say is welcome to insurance, pal. This sample policy provides no coverage when the hacker impersonates a service provider with whom you do not maintain a written contract. These critical nuances are everywhere. Watch out for them!

3. Hacker impersonates Michelle, the CFO at 123, Inc., one of your corporate clients, claiming that your employee made an error costing them $750,000. The hacker goes on to say that unless you wire $750,000, they will initiate a lawsuit against you and post negative reviews about you, damaging your brand.

Run the fact pattern through the four definitions to see if coverage applies to the CFO of a corporate client. Michelle would likely be considered a client because she is an employee at a company to whom your company provides goods or services. So, coverage is likely to apply because the hacker is impersonating a client.

4. Hacker impersonates an attorney at Lawyer & Lawyer PC, claiming that they represent 123, Inc., one of your corporate clients, in an action against you due to your error which cost them $750,000.

This one is much trickier than #3 above because Lawyer & Lawyer PC is not a client nor a vendor, and the attorney contacting you is not an employee or executive employee. However, you may have a strong argument that because they purport to represent 123, Inc. (who would qualify as a client), that they should be considered a client as well through a purported attorney-client relationship. You might say that they essentially stand in the shoes of your client. The insurer would counter that you do not provide professional services to the legal entity of Lawyer & Lawyer PC, so they cannot be considered a client. I do not know whether coverage would apply in this scenario, because both you and the insurer have strong arguments for and against coverage. Such a situation will probably end up as a coverage dispute in Court. The legal costs involved to dispute the coverage denial may eclipse the amount lost. At the end of the day, your company will have lost $750,000 (or more, especially if you fight to verdict and lose).

5. Hacker impersonates a federal IRS agent claiming the company is deficient in taxes, and that they will be subject to administrative fines if the taxes are not settled promptly.

Here, the IRS agent would meet none of the four definitions. A Federal IRS agent is not in your employment, so they cannot be an employee or executive employee. Your company does not provide goods or services to the IRS or the agent, so they cannot be a client. The IRS and the agent do not provide goods or services to your company, so they cannot be a vendor. As a result, if the hacker purports to be an IRS agent, there would be no coverage for the lost funds.

The possible scenarios are endless. Whom the hacker will attempt to impersonate is random, and depends entirely on what limited information they discover prior to committing the fraud. What is important is that you get a sense of how to evaluate the scope of coverage contained within your own insurance program.

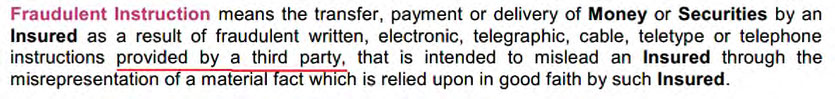

As an alternative example, consider the below coverage offered by another insurance company. It is vastly superior to the prior example in almost every way.

This insurer does not care who the hacker purports to be, so long as the instruction came from any third party with the intent to mislead. All the above scenarios would be covered with this language. This shows the importance of understanding the scope of coverage protecting your business, because, in our experience, losses have a habit of finding their way through the cracks in the insurance protection.

What Security Protocols were in place prior to the loss?

There are two main issues you must understand here. First, all carriers require that you describe whatever controls are in place when you submit your application for underwriting. The controls in effect at the time of the loss must be equal to or greater than whatever is disclosed in the application, or the insurer is going to deny your claim due to an underwriting misrepresentation. This implicit requirement is present in every policy.

The second issue is the question of whether or not your employee actually followed the protocols when the loss happened, or if the employee skipped them due to a perceived urgency. This is the critical issue. When the security protocols are in place, and are followed, then the fraud is almost always caught before the loss can occur. It is very hard to have a loss when security protocols (such as call-back verification) are followed. Losses occur when employees cut corners due to poor training or sense of urgency. Yet some policies exclude coverage for losses when the security protocols are not followed.

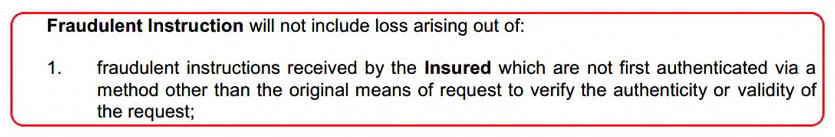

Here is an example.

Here, the coverage will not apply to any loss unless the employee first authenticates the request through what they call an “out of band” verification. Out of band verification means you must verify through a different type of communication than the original request, so if the original request is an email, the verification must be made through phone call, fax, or some other communication. If the original request was a phone call, the verification must be made through email, fax, or something else. If an “out of band” verification process is not included in the company’s wire transfer protocols, then they are severely at risk for a coverage problem if their policy contains the above language. An employee could follow the protocals to a tee and still fail to meet the requirements of the policy. Be careful to understand and address such requirements in your policy.

A special consideration for Trustees

Some companies out there wire client’s funds in amounts greater than $100,000 per instance. For these companies, traditional crime is unlikely going to be the proper way to insure the risk. Crime insurers are very hesitant to put up large limits (over $100k) covering the transfer of client funds. I have gotten around this in the past by writing dedicated Trustee’s E&O policies (with appropriate limits) under the theory that wiring client funds to a fraudulent location based upon a fraudulent request amounts to professional negligence. By converting the loss to a form of negligence, coverage may be obtained under the E&O policy. When placing such a policy, great care must be taken to ensure that the professional services definition is appropriate, and that the policy form is scrubbed of any exclusion related to the theft/transfer of funds, use of computer systems, or use of the internet. I have done this to great effect on certain accounts, and in one success story, our small Insured was reimbursed $1.2 million (less the retention) for a large fraudulent wire transfer loss of their client’s funds. Yes.. a hacker duped them into wiring $1.2 million of their client’s funds, and they fell for it! But the insurance paid, and their business lived to fight another day. With improper coverage this would have shut them down permanently. This shows just how important it is to carefully consider and review the insurance programs put in place to protect your business.

Sensei Says

You must carefully review the terms and conditions of your policy to understand how coverage will apply. Although we would generally recommend covering the loss under a crime policy because it is a theft of funds, you, as the Insured, should place coverage under whatever policy is giving you the broadest terms and conditions. Be on the lookout for highly restrictive factors like call back and verification requirements, as these conditions severely cripple the effectiveness and value of the coverage. Below are two final examples that you can use to test your new knowledge of the subject matter. I recommend giving it a try!

Test your Might

1. Jacob from Accounting is in charge of paying invoices on behalf of your company. Upon coming into work one morning, he receives an email from the company’s bank saying that there was some fraudulent activity on the account. The email then directs him to click a link, taking him to the bank’s webpage. The webpage asks him to input his log-in credentials to verify his identity and remove the lock on the company’s account. He inputs his username and password, and receives a notification on the next page that all issues have been resolved.

Unbeknownst to Jacob, this whole situation was a phishing scam devised by a hacker to steal the login credentials. As soon as Jacob entered his credentials on the website, the hacker used the newly obtained login credentials to log into the company’s online account at the bank’s real site. The hacker then initiates a wire transfer for $427,600 to destinations unknown.

Assuming coverage is in place with sufficient limits, what coverage would apply here? “Funds Transfer Loss” (where the Bank was duped) or Fraudulent Instruction (where you were duped)?

Although your employee Jacob was duped in this example, the hacker sent a fraudulent wire transfer instruction directly to the bank through the bank’s online banking portal. The hacker purports to be you, because they are issuing orders through your user account, having successfully phished the login credentials from Jacob. This is a Funds Transfer Loss because the hacker sent the instruction to the bank purporting to be you. The bank completed the transfer, believing it to be a legitimate request. Always focus on who sends the wire transfer instruction to the bank.

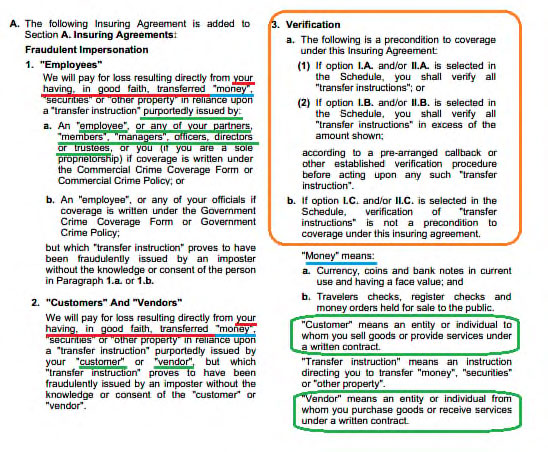

2. Here is an insuring agreement from a policy. Analyze it to answer the following questions. My walkthrough to follow.

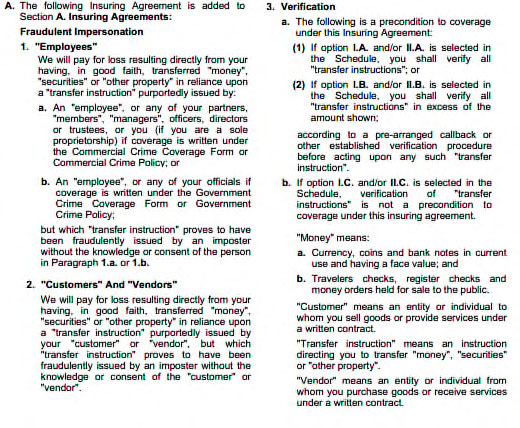

- What scenario is covered here? Where the Bank is duped by the hacker, or where your company is duped by the hacker?

- Whose money is covered? Does the coverage cover third party funds under your control?

- Are there any restrictions on whom the hacker may impersonate when committing the fraud?

- Are there any verification requirements?

Walkthrough –

- This coverage covers Social Engineering – when you are duped by the hacker into wiring money to a fraudulent location. The language in A.l and A.2 highlighted below discuss “your having, in good faith, transferred money based upon a [fraudulent instruction].” The

transfer is made by you, so this coverage will not cover a scenario where the hacker impersonates you and successfully dupes the bank into wiring money. Please see below highlights in Red showing the language. - Presumably this policy does not distinguish between your money and money in your possession belonging to someone else. As highlighted below in Blue, the insuring agreement just says “money,” as opposed to “your money.” Similarly, it just says “loss” rather than “loss by you” or “loss by the Insured.” The policy does not specify whose money the coverage refers to, unlike some examples provided above, so I would say the coverage applies to both your own money, and money belonging to a third party that you hold on their behalf.

- Yes. The hacker may only impersonate an Employee, Customer, or Vendor for coverage to apply. If they impersonate some other entity and successfully commit the fraud, you won’t have coverage under this policy. These terms are defined in the policy. Please see below Green highlights.

- Yes – but it depends on whatever box is checked on the coverage schedule. So, you have to first see what box is checked on the schedule to determine what part of this language will apply. The section has 3 different variables – A, B, or C. Whatever box is checked on the coverage schedule will govern the verification requirements. Under this sample policy, the verification requirement is a precondition to coverage. This means if you fail to satisfy the requirement, coverage is null and void. Please see below highlights in Orange.