Originally published on October 12, 2019 by Chris Quirk

What are Preambles?

Preambles are the clauses in a policy that determine the scope of coverage being provided or excluded. In Executive & Professional Liability policies, they are often the most important clauses in the whole document. More money has been paid or denied to insureds based on policy preambles than any other clause. There are countless court decisions that illustrate the importance that preambles have on the coverage provided by an insurance policy.

I like to visualize insurance as an umbrella in the rain (looking at you Travelers Insurance!). An umbrella protects you from the rain similar to the way that Insurance protects you from financial loss. If the umbrella canopy is too small, you’ll get wet. If the umbrella has holes that are too large, you’ll get wet. Preamble language is what determines how large or small the umbrella is (Insuring Agreement preambles), and how large the holes are (Exclusion preambles). Preambles are what dene the scope of the coverage and exclusions that will come into play if, or when, you should have a claim.

Preamble clauses typically affect only two parts of a policy: Exclusions and (to a much lesser extent) the Insuring Agreements. Preamble language tends to have some variety from Insurer to Insurer, but they typically fall in one of these three categories:

- “For” Preamble

- “Absolute” Preamble

- “Super-Absolute” Preamble

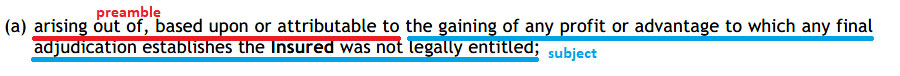

For this article, we will discuss these preambles in the context of a policy’s exclusions. Exclusions are typically broken down into two parts – the preamble and the subject. The subject explains the subject matter of the exclusion and the preamble defines the scope. Here is an example:

Effect of Preamble Wordings

The “For” preamble indicates a narrow scope, and is typically invoked by use of the word “for.” The “Absolute” preamble indicates a broad scope, and is typically invoked by the some version of the phrase “based upon, arising from, or attributable to.” The “Super-Absolute” preamble also indicates broad scope, and is invoked by some version of the phrase “based upon, arising from, attributable to or in any way connected to, directly, or indirectly, or in whole or in part.”

An exclusion containing a “For” worded preamble will only apply if the subject matter of the exclusion is the direct cause of the loss for which coverage is sought.

An exclusion containing an “Absolute” or “Super-Absolute” preamble will apply if the subject matter of the exclusion is a direct or indirect cause of the loss for which coverage is sought. In practice, there is not much difference between an “Absolute” or “Super-Absolute” preamble for the applicability of policy exclusions. With “Absolute” language, the policyholder may be able to find some arguments in favor of coverage, whereas “Super-Absolute” language will remove all hope for coverage. In both instances, insurers and US Courts will interpret them relatively alike.

To illustrate the effect of the different preambles, consider the following example. Suppose a software company develops real-time GPS positioning software for use in self-driving cars. Somehow, hackers infiltrate the company’s computer network and force a damaging update to the software, causing all systems running the software to malfunction. This leads to cars driving themselves off road, and people sustaining serious injuries or even death. The company loses many client contracts as a result of the fiasco and may not be able to continue operating in this space, if at all. As a result, the company faces a slew of litigation, which can be broken down into the following types:

- Suits by private plaintiffs who sustained injuries when their cars drove off the road.

- Suits by the company’s shareholders alleging that the D&O’s mismanaged the company by not having the right computer security or safeguards in place.

- Suits by car companies who utilized the company’s software, and now have to recall cars to install replacement software, leading to significant recall and business interruption costs. As a separate count, they also sue for the costs involved to repair or replace those cars that sustained physical damage.

Assume the company carries D&O insurance and wishes to submit the lawsuits to the Insurer for coverage. The D&O policy has a bodily injury and property damage exclusion. In this situation, the Loss with respect to the Insurance Policy are the different lawsuits. For each suit, let’s try to determine whether or not bodily injury was a direct cause or indirect cause, as this is the first step in understanding how the different preambles will affect the applicability of the policy’s bodily injury exclusion.

SUITS BY PRIVATE PLAINTIFFS WHO SUSTAINED BODILY INJURY

These are lawsuits against the company for actual injuries sustained in a crash – plaintiffs sue for medical bills and other related losses. The plaintiff’s bodily injuries are the primary agent leading to their lawsuit against the company. Without the injuries, they would not have filed a lawsuit and there would be no loss for which the Company would seek coverage under the policy. As a result, we can determine that the plaintiff’s injuries are a direct cause of their lawsuit against the company.

All three preamble versions when applied to the bodily injury exclusion will exclude this claim because the plaintiff’s bodily injuries are a direct cause of their lawsuit against the company. The D&O insurer will not cover these lawsuits no matter which preamble is used. The only way for there to be coverage is if there were no bodily injury exclusion at all.

SUITS BY SHAREHOLDERS ALLEGING MISMANAGEMENT BY THE COMPANY’S D&OS.

This one is a little trickier. What is the direct cause of the shareholder’s lawsuit in this situation? Although not specifically mentioned, it’s the financial consequences sustained by the company and subsequent damage to the shareholder’s investment. This is what creates liability to the shareholders, not the bodily injury itself. Employees can get hurt at work without substantially disrupting the company’s business, and thus without leading to shareholder liability. Liability to shareholders will generally attach only once the company’s financial position is damaged.

But the breach and injuries sustained by the plaintiffs are what is causing the company’s dire financial situation, right? Yes, but it’s one step removed from the shareholders. It’s the “cause of the cause.” No shareholders allege that they personally sustained bodily injury; rather they allege that their investment has been damaged and that the D&Os are to blame. The breach and subsequent injuries are a direct cause… of the company’s dire financial situation and damage to the shareholders’ investment, which itself is a direct cause of the shareholder lawsuit. As such, the bodily injuries are actually an indirect cause of the shareholder lawsuit.

In terms of coverage provided for the shareholder lawsuit, a D&O policy having a “FOR” worded bodily injury exclusion would provide coverage for this lawsuit because that exclusion only applies when bodily injury is the direct cause of the claim. As mentioned above, bodily injury is an indirect cause of the shareholder’s suit, but it is not the direct cause. The direct cause is the company’s financial performance and damage to the shareholder’s investment.

If the D&O policy had an “Absolute” or “Super-Absolute” preamble, then the shareholder lawsuit would be excluded because bodily injury is an indirect cause of the lawsuit.

SUITS BY CAR COMPANY CLIENTS WHO UTILIZE THE COMPANY’S SOFTWARE

These lawsuits have two components to them. The rst is the cost to repair or replace those cars damaged as a result of the malfunctioning software. The second is the economic loss associated with recalling cars and replacing the software.

The first component of the claim is going to be excluded by all three versions of the property damage exclusion because property damage is a direct cause of these claims. If the cars had not sustained damage, they would not have had to be repaired or replaced. As such, there would not have been a suit against the company for these losses.

The second component would not be excluded by a “FOR” worded preamble because bodily injury is not a direct cause of these losses. The direct cause of these losses are the time and money spent by our customer, the car company, to provide recall services to their customers.

The second component is likely to be excluded by an “Absolute” worded preamble because the Insurer is likely to say that bodily injury is a direct cause of the car company having to do a recall, and thus an indirect cause of the suit. They are likely to argue that the car company issued a recall specifically to avoid future bodily injuries, and so the suit does arise from bodily injury as an indirect cause. This is usually a winning argument, but if the exclusion has an “Absolute” preamble, then the Company may have the opportunity to provide evidence showing that the recall was ordered for reasons independent from avoiding past or future bodily injury. One example might be a news bulletin advertising the recall for totally unrelated reasons on a date prior to the company’s hack. A court might look at this evidence and say that the recall does not arise out of bodily injury because it was planned prior to the injuries being sustained, and thus rule that bodily injury is not an indirect cause of the recall. Obviously this is extremely circumstantial and the company would have to get lucky.

If the bodily injury exclusion had a “Super-Absolute” preamble, the second component would be excluded no matter what, even if there was evidence that the recall was planned prior to the hack. The “Super-Absolute” preamble would eliminate all possibilities of coverage through the words “any way connected to, directly, or indirectly, or in whole or in part.”

Secondary Effects

A secondary benefit of “For” worded exclusions is that if a suit is led including both covered and excluded counts, you may be entitled to an allocation. When you buy an indemnity policy (which refers to the way defense and payments are handled), a suit count that is excluded by a “For” worded exclusion will not infect and preclude coverage for other covered counts. The insurer will allocate the loss for covered counts and pay accordingly.

If a suit has a count that is excluded by an “Absolute” or “Super-absolute” exclusion, the excluded count may infect the entire lawsuit, meaning you may not have coverage for any part of the suit, even if some counts would be otherwise covered by your policy.

In Duty to Defend policies, courts have restricted the ability of uncovered claims to infect other covered claims, even if the applicable exclusion has an “Absolute” or “Super-absolute” preamble. An insurer may have to provide defense for excluded counts as long as a single covered count remains alive in the litigation. Duty to defend policies have an advantage over indemnity policies in this regard. The downside to Duty to Defend policies is that the Insurer controls the defense, which includes selecting defense counsel.

What about Insuring Agreements?

The logic essentially stays the same, but now we are concerned with coverage grants, so broader is better. “For” worded insuring agreements lead to narrower coverage grants, whereas “Absolute” preambles give broader coverage grants. I haven’t seen “Super-absolute” insuring agreements, though.

Sensei Says

There is no uniform interpretation for the applicability of these preambles. There are countless Cases in the Executive and Professional Liability world, and even more in the Commercial General Liability world, where Courts discuss and interpret preambles on both coverage grants and policy exclusions. This article does not take into account the nuances provided by the mountains of case law on the subject and is only meant to provide a foundation that you, as the policyholder, can use to have a more meaningful impact on your insurance decision-making.

The difference between “Absolute” and “Super-Absolute” is minimal. Even if you have an “Absolute” preamble and strong arguments in favor of coverage, you will end up in Court fighting your insurance company rather than defending the actual claim. The case can drag on for a long time, incurring separate uninsured legal fees, and may not even resolve in your favor. In general, it is usually advantageous to obtain “For” worded preambles on your policy exclusions in lieu of “Absolute” or “Super-Absolute” ones. You won’t be able to get “For” worded preambles on all exclusions, so you should focus on those exclusions that are most relevant to your business operations. If your insurance carrier asks for an additional premium to make the change, it’s almost always worth it.